Democracy by Design: How 2025 Redistricting Is Choosing America's Future

Every ten years, the release of new census data asks state legislatures to redraw their political maps to reflect shifting populations and preserve equal representation. In the lead-up to the 2026 midterms, an unprecedented mid-decade redistricting battle has broken out across the United States. Governors and state legislatures have begun drafting new district maps in an attempt to consolidate power in preparation for one of the most contentious midterm elections in years.

As midterms have historically disfavored incumbent presidents, President Donald Trump urged Governor Greg Abbott (R-TX) and his Republican colleagues in Texas in July 2025 to redraw the state's congressional maps with the goal of creating five additional Republican-leaning seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. After Texas Democrats staged a two-week walkout to protest the new redistricting proposals, the Texas Legislature approved a new congressional map by an 88-52 vote, eliminating five Democratic districts and handing Republicans 30 of the state's 38 seats.

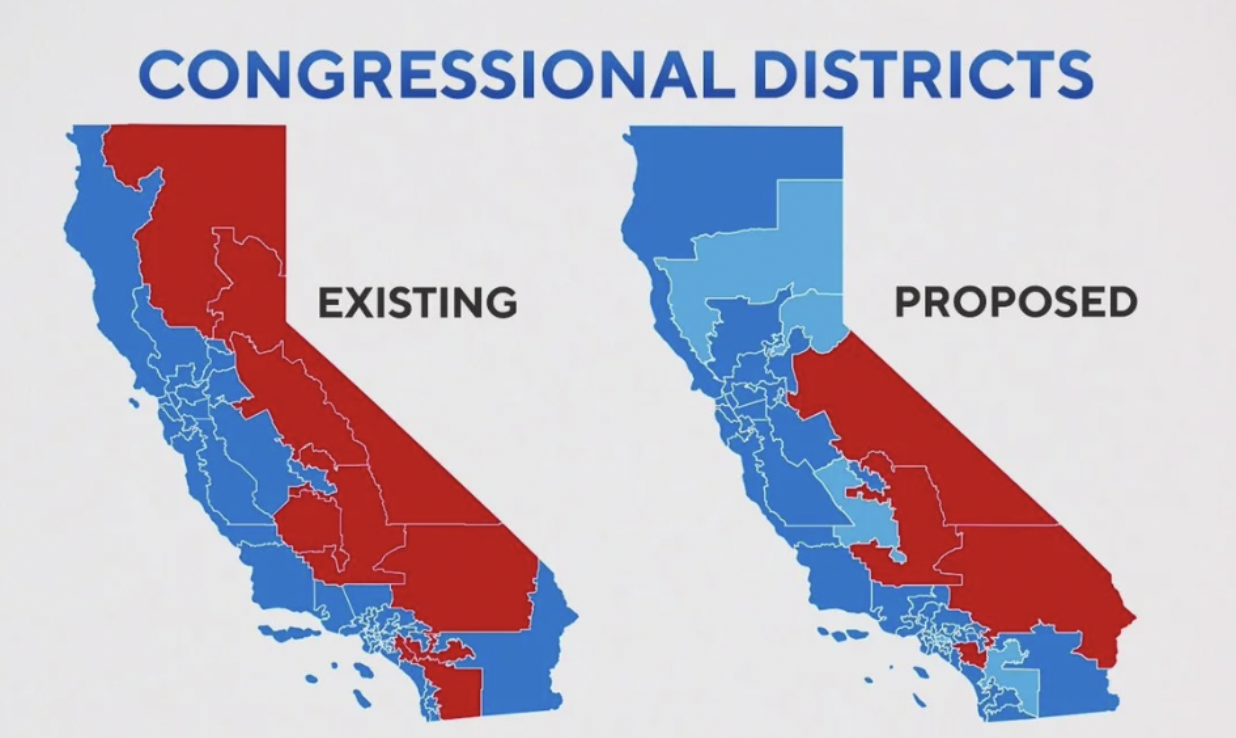

In response to the Republican gains in Texas, Governor Gavin Newsom (D-CA) successfully redrew his state’s congressional map. Passed by the legislature and recently voted into law by California voters thanks to Proposition 50, California’s new map created favorable voting conditions for Democrats in five seats currently held by Republicans in Orange County and Eastern California. The proposition passed with 60 percent of the vote and allows a temporary modification of the state’s constitution. This modification replaces the current congressional district map drawn by California’s Independent Redistricting Commission with a new one drawn by the State Legislature.

Source: CBS News

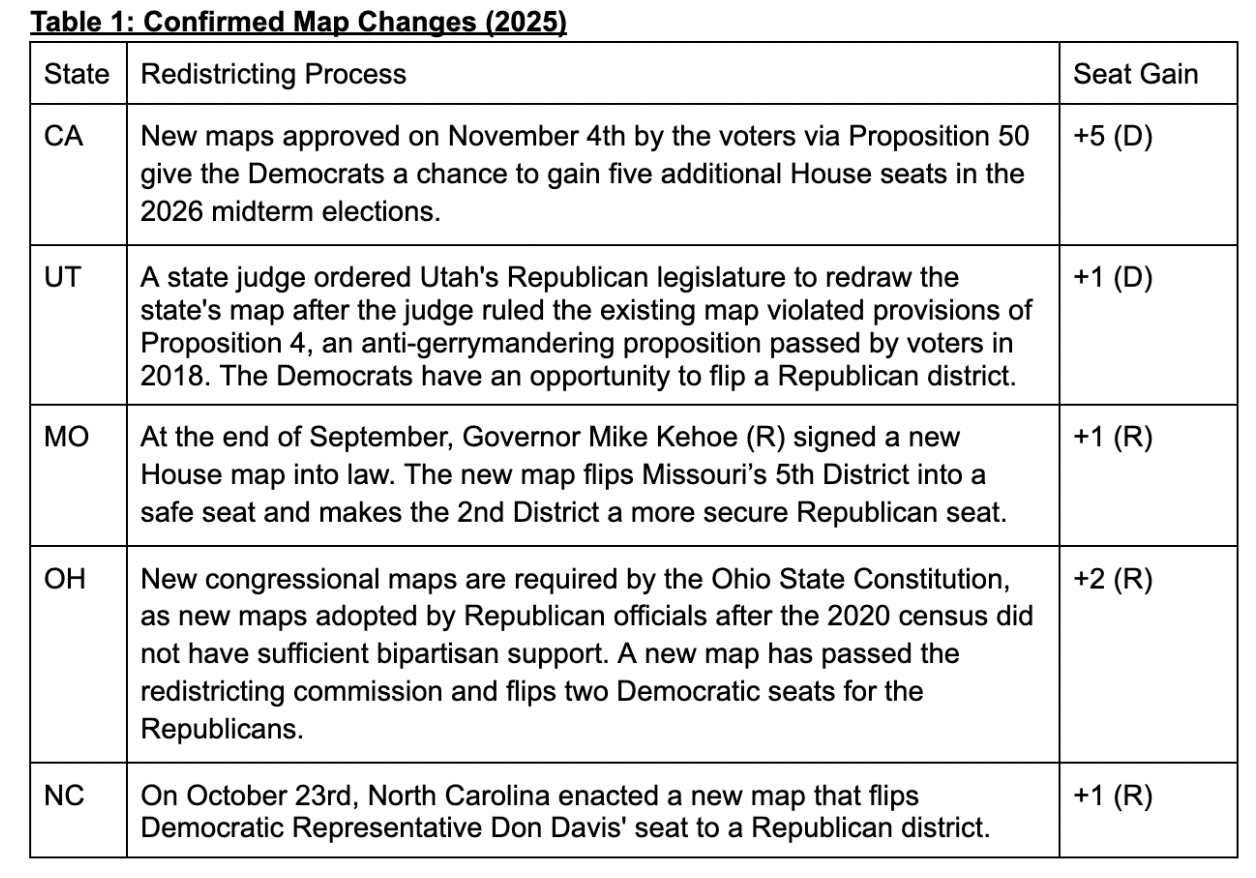

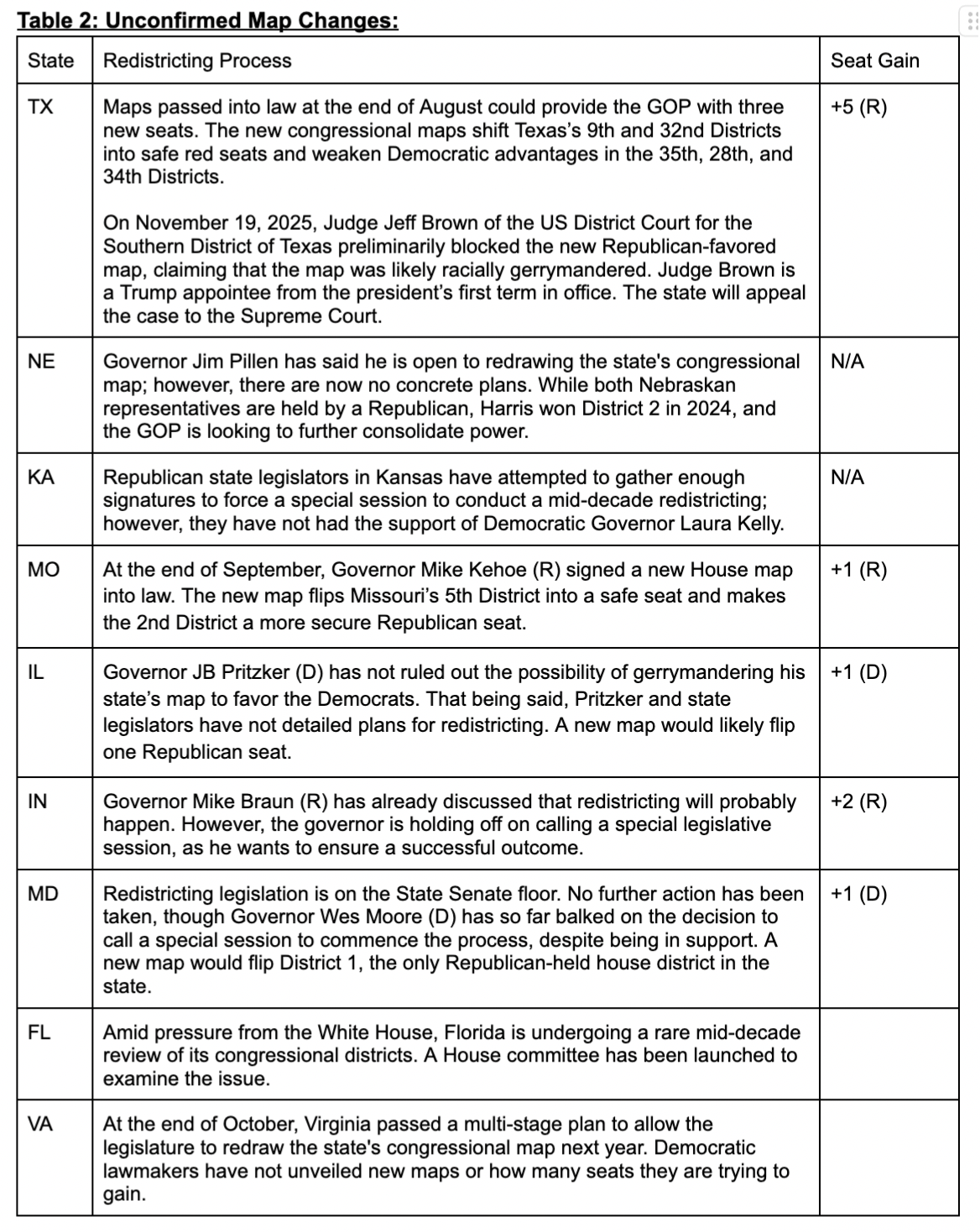

As of November 7, 2025, states with Republican-leaning legislatures of Missouri, Florida, Ohio, and North Carolina have joined Texas in adopting redistricting plans. In Utah, the state court ruled that the existing map violated provisions of an anti-gerrymandering ballot measure, ordering the Republican legislature to redraw the state’s map. Simultaneously, blue-leaning states such as Maryland, Virginia, and Illinois have signaled their interest in redistricting: a list of states conducting redistricting can be found in Table 1 below.

Although the current redistricting process has created uncertainty, it remains partially subject to constitutional limits. The 14th Amendment prevents states from drawing districts that unjustly dilute the votes of certain populations. Within the amendment, Article 1 requires that the districts must reflect population changes after each census. The amendment is known for its part in Baker v. Carr (1962). Charles Baker, a Republican from Shelby County, Tennessee, sued Secretary of State Joe Carr (D), arguing that Tennessee’s failure to update its legislative districts resulted in districts with vastly unequal populations, violating the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The Supreme Court overruled the U.S. District Court’s statement that Baker lacked jurisdiction and justiciability and further ruled that the state had failed to apportion its district in an equal fashion and did violate the 14th Amendment. The follow-up case, Reynolds v. Sims (1964), explicitly required that state legislature districts have equal populations with deviation to respect municipal boundaries, prior districts, or compliance with the Voting Rights Act: a 1965 law prohibiting redistricting plans from diluting minority voting strength.

Redistricting laws were further ruled upon in Rucho v. Common Cause (2019). State Senator Bob Rucho and the architects of the North Carolina congressional map openly admitted partisan intent and stated that the goal was to create ten Republican House seats and three Democratic House seats. In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court held that while partisan gerrymandering was “distasteful” and “unjust,” the Constitution does not provide the Supreme Court with a judicially manageable standard. In the majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts stated that curbing partisan gerrymandering was an issue for Congress and state legislatures as per Section 4 of Article 1. Rucho v. Common Cause. This ruling effectively removed federal courts from policing partisan gerrymandering and forced the legislative branch to be the judges of ethicality. As a result, the fairness of congressional maps now depends almost entirely on the political incentives of those drawing them, rather than on federal judicial oversight.

As state legislatures and political parties weaponize geographical redistricting to secure partisan gains, the evolution and current state of redistricting reflect the broader tension in America’s political climate. In a system designed to be limited by checks and balances and separation of powers, the Supreme Court has stepped aside. Their absence has paved the runway to create a future skewed away from democratic representation and the will of the people. While maps, districts, and data may lack the glimmer of hot-button policy issues, the battle over redistricting carries lasting consequences: respecting the will of the people and preserving the core functions of our democratic republic.